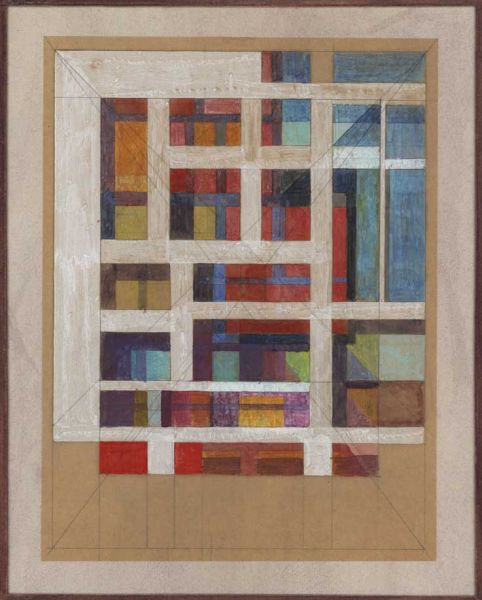

Sir Thomas Monnington (1902-1976):

Geometric Study, circa 1964

Passe-partout (ref: 3379)

Pencil, watercolour and white chalk on paper

11 x 8 1/2 in. (28 x 21.5 cm.)

(13 x 10 3/8 in. (33 x 26.5 cm.)framed)

See all works by Sir Thomas Monnington chalk pencil watercolour

In a gilded square section frame mounted within a glazed gessoed shadow box with a matching gilded outer moulding.

Monnington's studies for his 'Geometric Paintings' (as he preferred to

call them) are works which he crafted meticulously. He frequently

reworked the same design over and over again before producing a version

in tempera. 'I do feel that as President of the R.A. I should show at

least one painting there a year .. I take a long time to resolve a

painting problem. I take a year to do one painting because I make

innumerable studies preparing the way' (Sunday Express, 19 Oct 1969).

Monnington was significantly the first President of the Royal Academy

to paint abstracts, and inevitably his work was not always well

received:

'The President is indeed a charming man but his work is an

embarrassment. I can only recommend it to some linoleum manufacturer.'

So wrote Terence Mullaly, reviewing the Royal Academy Summer Show

(Daily Telegraph, 28 April 1967)

Unlike his predecessors, Monnington was prepared to throw open to

debate questions about contemporary art. 'I happen to paint abstracts,

but surely what matters is not whether a work is abstract or

representative, but whether it has merit. If those who visit

exhibitions - and this applies to artists as well as to the public -

would come without preconceptions, would apply to art the elementary

standards they apply in other spheres, they might glimpse new horizons.

They might ask themselves: Is this work distinguished or is it

commonplace? Fresh and original or uninspired, derivative and dull? Is

it modest or pretentious?' (Marjorie Bruce-Milne, The Christian Science

Monitor, 29 May 1967).

At the same time Monnington was keen to defend traditional values. 'You

cannot be a revolutionary and kick against the rules unless you learn

first what you are kicking against. Some modern art is good, some bad,

some indifferent. It might be common, refined or intelligent. You can

apply the same judgements to it as you can to traditional works,'

(interview with Colin Frame, undated newspaper clipping, 1967).

Rome Scholars

Rome Scholars SOLD

SOLD